|

I tried hard to avoid COVID and was successful until I wasn’t. It finally caught up with me a few weeks ago. I don’t know about you but when I’m sick, I get so many visitors and most of them aren’t invited. I’m not talking about family and friends bearing fresh squeezed orange juice and chicken tortilla soup, more like the visitors in Rumi’s poem, The Guest House, “the crowd of sorrows who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture.” There’s something about lying in bed, feeling icky, and staring at the ceiling or the backs of my eyelids, that invites what feels like bad company. I’m a captive audience and there literally is “nothing to do, and nowhere to go.” Sharon Salzberg, teacher, author, and co-founder of Insight Meditation Society, has a way of saying things that just cut through to the truth. One of them is, “Sometimes it just hurts.” Being sick hurts. It’s an arrow that pierces our tender parts and often we shrug it off while we internally and silently struggle. I think it’s the silent struggle that brings all the visitors. In my recent illness there were body sensations that made me want to abandon ship and go live in different skin, difficult emotions that floated in like bad weather, and memories that took me to dark places—a different pandemic, HIV/AIDS, and the memory of watching my mom die from COVID complications. These visitors were fodder for a whole quiver of arrows that I self-administered. The Buddhist say the first arrow of suffering is the hard stuff of life that is just part of living but the multitude of arrows that come next are often the one’s we self-inflict. The wounds of our lives become scabs that can be weaponized by our dear, old, overactive, survival brain in a misguided attempt to protect and save us from these resurrected and perceived threats. Often it ends up as some form of self-judgment or self-criticism and so the initial hurt becomes a full-on self-attack. “If I wasn’t so _____, I’d be _____.” Thankfully this isn’t the end of the story. Wellness or well-enough is not a passive process. If we remember to listen, there is an invitation to participate in our own healing with the resources of presence and compassion. It feels like grace because it comes from beyond and yet it’s an inside job. In a moment of grace, there is a pause, a bit of space, that creates possibility. For me this was a moment when the visitor didn’t fill up the full aperture of my awareness, and I was able to see a glimmer of something just over their shoulder, a little light, a soft breeze, a being on the other side looking at me with a warm and caring gaze. And in this awareness was the understanding that the “crowd of sorrows” didn’t travel alone! Just behind grief there was love, accompanying a body in distress was a faithful inhale and exhale, Jesus was holding a scared boy’s hand, and shame was disco dancing with a leprechaun. It wasn’t a cure but there was room for moments of connection and love. Fred Rogers used to tell kids on his television show, Mister Roger’s Neighborhood, “Look for helpers.” What if being sick was about looking for helpers? They just might be behind the visitors we didn’t invite. The Guest House

Rumi This being human is a guest house. Every morning a new arrival. A joy, a depression, a meanness, some momentary awareness comes As an unexpected visitor. Welcome and entertain them all! Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows, who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture, still treat each guest honorably. He may be clearing you out for some new delight. The dark thought, the shame, the malice, meet them at the door laughing, and invite them in. Be grateful for whoever comes, because each has been sent as a guide from beyond. Jalaluddin Rumi, translation by Coleman Barks (The Essential Rumi)

0 Comments

A beautiful question is the one we don’t know how to ask, yet it is as essential as breath itself. It lives beyond the words that get stuck in our throats and like a sunrise it moves our hearts before we speak. David Whyte, poet and author, says, “The ability to ask beautiful questions, often in very unbeautiful moments, is one of the great disciplines of a human life. And a beautiful question starts to shape your identity as much by asking it as it does by having it answered.” A beautiful question carefully disrobes our disbelief and despair and reveals an unspoken possibility. Like poetry it can leave us feeling naked, alive, and holy. I have lived through two pandemics. The other one commemorated the 35th anniversary of the AIDS Memorial Quilt this weekend. To mark the anniversary, San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park held the largest display of the Quilt in several decades (3000 individual panels). I arrived in the morning as groups of people milled about the Robin Williams Meadow waiting for the sun to dry the dewy grass. A grid was mapped out in the field with bundles of fabric in the middle of each quadrant. The sun was soft and kind. Eventually groups of volunteers began to carefully unfold the precious packages, like origami in reverse, smoothing each crease and returning each bundle to its natural state. Each panel was stretched from north to south, and east to west, a silent testimony of names laid out in repose. Each 3x6-foot panel, about the size of a grave, is stitched together with eight others into a collage of colors and images. The entirety of the Quilt contains over 50,000 individual panels, weighing an estimated 54 tons, and representing over 110,000 people lost to AIDS. Photo credit: Jorg Fockele As I watched this exquisite unfolding of care, I thought about one of the anthems of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, “Seasons of Love” from the Broadway musical, Rent. Five hundred, twenty-five thousand, six hundred minutes Five hundred, twenty-five thousand moments so dear Five hundred, twenty-five thousand, six hundred minutes How do you measure, measure a year? In daylights, in sunsets In midnights, in cups of coffee In inches, in miles In laughter, in strife In five hundred, twenty-five thousand, six hundred minutes How do you measure a year in a life? In those early years of HIV/AIDS, the unbeautiful moment was not how to measure a year in a life but rather how to measure a life in just one year. Many of us were told we had a year. Too many only got a year. As it turned out my name didn’t make it onto the Quilt. I am one of the fortunate ones whose panel is still being sewn. And in this more recent pandemic, over a million people in the United States gone, COVID gave even less time to measure a life. Mom had two weeks. Both diseases have had so much suffering, isolation, blame and shame. A beautiful question is not pretty or easy. It shakes the ground with what is hiding in plain sight. “Seasons of Love” answers its own question with a beautiful question. How about love? How about love? Seasons of love Recently one of my dear friends asked, “What if love were enough?” Love? I can hear the groans and see the eye rolls. It’s easy to become jaded. But perhaps this is not a problem with love, it’s a problem of our imagination. Sharon Salzberg in her book, Real Love: The Art of Mindful Connection, suggests that love is not just an emotion, it’s a skill. We don’t fall into real love. It’s a choice. It requires practice and intention. This kind of love is an audacious conversation with our dreams. How about love? What would that look like? “And now abide faith, hope, love, these three; but the greatest of these is love.” 1 Corinthians 13:13. What if we lived that? As I consider my seasons, love is always what has saved me. Perhaps we never have enough love. Perhaps love is always enough. How about love? I didn’t plan on this being a Valentine’s Day blog. Like most of us, I have a complicated relationship with love. Yes, love is wonderful, and it also inevitably includes love’s shadow—sorrow. This is not necessarily a sign that something is wrong. The flavor of love is bittersweet. My parent’s wedding anniversary is Valentine’s Day, and they are gone. Harold and Milly loved well, which is to say enough, and I am a grateful descendent of their love story and . . . mom will never again put leftovers of my raspberry, lemon, buttercream anniversary cake into the freezer and write a label with her careful penmanship, “David’s Yum Yum.” You can’t have sweet without the bitter –they are fused in magic kitchens that bow to their alchemy. “It’s so easy to fall in love. It’s so easy to fa-all in love.” The music flew past me on a bicycle. Yes, that 70’s Linda Ronstadt version of the Buddy Holly anthem, full throated and testifying from a boom box duct taped to a bike. A man with a long gray ponytail hanging out the back of his bike helmet was riding down the sidewalk. His Birkenstocks pumped the pedals and his whole body swayed with Linda. He SHOULD have been riding in the street, Page Street, a “slow street,” designed during the pandemic for limited cars and neighborly speeds to create more room for people to move with their own locomotion. I didn’t say it, but I thought, Get off the sidewalk. Idiot! (OK, I probably thought a different word). And yet something else appeared alongside my clenched gut and sidewalk policing. There was a faint whiff of my 2022 intention—look for goodness. . “It’s so easy to fall in love.” Could the message have been any clearer? I broke into a smile. The couple walking towards me from the opposite direction were looking at each other with big grins. As we approached, our smiles found each other like lost friends. At the corner traffic light, a group of gangly teenagers from a nearby High School waited, danced, and laughed with our bike messenger. They recognized the music’s invitation and couldn’t help themselves. When was the last time you fell in love with a moment? And did you pause and really taste it? Because I lingered, the memory of that wonderful and kooky encounter now lives in my body as a smile. It feels like a moment of grace because I didn’t create it, I just received it and blessed it like a welcomed breeze. I’m not always so receptive. Turns out, it’s not so easy to fall in love because normally I’m trying to make it last forever or I’m not even looking. I’m more likely to be looking for its absence. “It’s so easy to fall in fear.”

The challenge is that we have what Rick Hanson Ph.D., calls a negativity bias. Our neurology is hardwired to look for problems. The survival instinct kicks in when we perceive a threat, and our central nervous system readies our most powerful and primal defenses, fight, flight or freeze. This is great when a danger needs our immediate and automatic reaction. It’s less helpful when the danger is within our social-emotional world, and we need help from our more evolved brain where things like compassion, empathy, discernment, and perspective live. This is where my 2022 intention matters. Having the intention to pay attention to naturally occurring goodness, the sun on my face, the smile of a stranger, a bicycle singing a love song, or the delicious homemade ramen I made last night for a party of one—me, is a way of balancing my negativity bias. In psychological terms this is called savoring—lingering with a good experience for 15-20 seconds and then letting it go. It’s the way a good experience becomes a good memory. A friend of mine calls these moments of goodness, “God surprises.” These surprises are up in clouds with a flock of noisy wild San Francisco bright green parakeets, and down in the dirt, munching with the earthworms so spring seedings will sprout. As Rumi says, “There are a hundred ways to kneel and kiss the ground.” What if falling down didn’t always have to hurt? What if it were a voluntary supplication, little by little, kindly bending my knees to wonder and goodness? What if even during a pandemic I could sometimes hear Linda’s voice with soft ears, “It’s so easy to fall in love?” I. It feels like a Seurat painting as I sit on a park bench in Golden Gate Park, under clear blue sky, soft autumn sun, water splashing in the fountain and movement of people under a canopy of leafy pollarded trees. But this is not dots of paint on a canvas, this tableau breathes. I hear his shuffling feet before I see him, his clothes hang baggy on a skeleton frame, aged or ill or both. Alongside him, a Golden Retriever with that telltale senior white face walks as slow as his human but turns his head toward me with that Goldie longing, “Love me.” The man interrupts the wish and firmly and simply says, “No.” The Goldie obeys and lumbers on. Sitting on other side of the fountain, a young woman stares into space with an infant held close against her chest, a small blanket covers the baby’s head and the mother’s breast, tiny legs poke out from under the blanket and pump with excitement. How does all this co-exist? What kind of alchemy happens in the heart to make room for it all. I want to cry and smile. I want to protest and embrace. II. We buried mom last month. The twelve-inch square was perfectly carved into the Wisconsin fertile soil. After eleven months of COVID quarantined grief, we finally were able to gather as a family and return her ashes to the earth. She lies next to dad, next to my brother, we were a family of seven, now we are four. The hills surrounding the cemetery were filled with oak, maple, aspen and sumac in their autumn show-off colors but muted by a gray sky. We offered careful tears and polite pauses when words couldn’t be formed. I wish we had been able to gather sooner when grief had no patina, when it was fresh and raw—the kind where all you can do is hold on to each other. But over these last eleven months, we have grieved separately and alone as best we could. That intense moment of loss has passed. I am grateful it has. I wish it hadn’t. As I dropped my pink daisy into the grave, part of me wanted to fall into the hole with mom. And then the memorial was over—officially orphaned, waiting for what’s next. I buried my hands in my pockets, my heart looking for a place to land. Nowhere to go but here, making contact and covenant with me, the one who needs to be mothered. And so, the mother becomes the son. Meanwhile across this landscape a million leaves, the color of sunset, were making their transition. Soon knobby limbs would be bare and frosted with snow. And then after a long sleep, by some unspoken agreement, spring will course through those same branches and buds will reach for summer green. Life during death and death in the living. Love and sorrow together again. Love Sorrow Mary Oliver Love sorrow. She is yours now, and you must take care of what has been given. Brush her hair, help her into her little coat, hold her hand, especially when crossing a street. For, think, what if you should lose her? Then you would be sorrow yourself; her drawn face, her sleeplessness would be yours. Take care, touch her forehead that she feel herself not so utterly alone. And smile, that she does not altogether forget the world before the lesson. Have patience in abundance. And do not ever lie or ever leave her even for a moment by herself, which is to say, possibly, again, abandoned. She is strange, mute, difficult, sometimes unmanageable but, remember, she is a child. And amazing things can happen. And you may see, as the two of you go walking together in the morning light, how little by little she relaxes; she looks about her; she begins to grow. III.

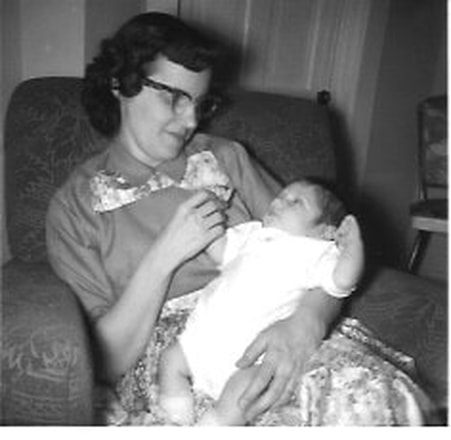

November 19 is the one-year anniversary of mom’s death. Anniversary isn’t exactly the right word—it doesn’t have the right balance of grief and gratitude. But I’ve been thinking about those mother moments that are so ordinary yet made extraordinary because of their repetition and faith. It’s a kind of magic that you don’t understand in the moment but it becomes the air you breathe and the ground you walk on. Tucked In David Fredrickson The day is ending Covers pulled tight Tiny heartbeats wait And then she is there Sitting beside Or bending low Often a prayer But always a kiss Good night And just like that Into the dark night I’d go Being loved Her breath and prayer Placed on brow or cheek Again, again, again Unremarkable Unforgettable I miss the way mom championed us—her family. In her later years her patchy memory only remembered the good, even as she reminded us with a twinkle, good is not perfect. The worries that kept her awake at night and the wishes that in some ways we would be different went with the memory of what she had for breakfast. She thought of us as gifts. A good gift is larger than the package of perfection. It’s not an object, it’s a verb that keeps creating. When I lay down for my final rest, I want it written, “I was loved.” I’d like to tell you that I’ve got things figured out. The mind would love to have answers that are linear and repeatable. The heart, on the other hand, takes a more circuitous route because it lives in the forest where doers do not tread but with beings who wander, guided by seasons and the tug of the moon. Since I’ve gotten my first vaccine, I’ve been thinking about what happens when COVID as we know it is behind us. I have a feeling that I’m going to find that joy and relief have company from their murkier cousins, anger, numbness, sadness and confusion. I think my body has some limbic residue. Over the year, I’ve feared the very air I breathe, felt the divide between people become even more hateful, hurtful and cavernous, and watched mom in her nursing home room, unable to hold her hand, die on a Zoom screen. What happens when fight, flight, freeze have nowhere to go? In gentler times when the danger abates the nervous system regulates, but these stress responses have been stuck on “on.” As a result, I know I will have to go through some stuff before my body metabolizes this last year. I come to this honestly—they’re called survival defenses for a reason. But the body keeps score to use the title of Bassel van der Kolk’s seminal book* on trauma and the body. So, I decided to do a self-led, home-based 4-day silent retreat. I used Natalie Goldberg’s, longtime Zen practitioner and author, retreat structure, “Sit, Write, Walk,” alternating between sitting meditations, writing meditations and walking meditations. I’ve had a lot of silence this year but it’s different when you make it an intention. The retreat was not easy. Mother Teresa said, “God is silence, prayer is listening.” Well, my listening felt like trying to find a radio station while driving through the middle of Nebraska. My static had serious cravings for my go-to distractions—just a peak at the NYT, a skip around on the Internet, maybe email or Facebook, call someone, what’s on Netflix, has the refrigerator gnomes left any goodies since last time I looked? The difference was that with my intention of silence, I noticed. There is something that shifts when we deepen our attention. It’s not like taking a Tylenol. It moves on its own time, but it moves. So, in the midst of my struggle and following a bad night’s sleep, I made my breakfast of champions—savory steel cut oats. I made them slow, nowhere to go, nothing else to do, smelling, tasting, feeling each step. Chopped onions and celery sautéed until translucent and just beginning to caramelize, added chopped garlic, cilantro and jalapeño peppers cooking until fragrant, added diced carrots and broccoli, pureed sweet potatoes, stock, and cooked steel cut oats, and then simmered until the vegetables were just tender. Finally, topped it off with a soft poached egg. I hope this sounds as good as it was! Then I hiked to Twin Peaks. For those who aren’t familiar, it’s one of the highest points in San Francisco with a 360° view. Breathtaking on a clear day and on this day, it was gloriously glistening. I laid down a blanket and got myself into lotus position (or close enough) and began a lovingkindness meditation, sending kindness and compassion (our superpower) to myself and to those who came into my mind’s eye. At some point mom appeared but I could only see the back of her head. It seemed she had somewhere to go. Most of my grief over these last four months has been tight, broken and sharp. But on this spring day, when California poppies dotted the hillside and there was a soft breeze of fresh Pacific Ocean air, something shifted. I wanted to choose spring. No one told me it was time, but the dirt, rock and sky sent an invitation. I loved the sun and let the sun love me back. I sensed the spring flowers like promises I thought would not be kept yet they were singing. Yes, my trip around the sun included winter, fear and death but also this—new life and possibility. I told mom that I wanted to dance with the bumble bees and hummingbirds as they flew from flower to flower with their moans and urgent kisses. “Gimme some of that Kool-Aid,” I chuckled. And Mom began to float away. For that moment, I let her go with a slight smile. Something in my body released, just a bit. There would be tomorrows with other fragments of grief but on this day, two weeks after the vernal equinox, I chose spring. * Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, (Penguin Random House, 2015) If spring had a sound track . . . James Taylor and Yo-Yo Ma "Here Comes the Sun" Mildred (Milly) Marie Fredrickson April 24, 1924--November 19, 2020 I don’t want to Say it This pen feels heavy and this thumb and forefinger are attempting a sit-down protest. To write it, is to make real that which wants to remain a dream. When asked, “How are you?” dad used to reply, “I think I’m OK, and I hope I’m not lying.” Dad, I think I understand. I don’t want to lie but the ground keeps changing as my heart keeps breaking. Words are clumsy tools when trying to give names to the liminal space between love and sorrow. Too loud Too quiet Mom died last month It still gets stuck in my throat. I refuse to swallow and then I do. The body’s reflex to make room for another breath wins. My siblings and I had been calling her every night since the early days of COVID—a conference call that often included all four of us but always some of us and often went on for more than an hour. We read her letters, remembered stories, told her of our lives, witnessed her loneliness and unease and celebrated her life and love which is to say her grace and resilience. The calls were like long, slow family dinners, garden-raised, home-cooked meals of our childhood, talking at the same time, silence, laughter, loneliness in togetherness, and winces of pain. And then in late September she fell and broke her hip. The fracture was so severe that the only way to manage the pain was surgery. Remarkably at 96½-years-old she made it through surgery and was making a remarkable recovery. However, when she returned to the nursing home, they had a devastating COVID outbreak and mom became positive. Even though she made it through the infection period, it was all too much, and she died several days after her quarantine. Bone of my bones Flesh of my flesh A dream without the dreamer Death never lands easy but during the isolation and restrictions of COVID . . . well, we did the best we could. We sat vigil with her on Zoom for several days before her death. There were awful moments of suffering where she was lost in her pain, but she knew we were present. We sang, prayed, read, talked, cried, and sat . . . and sat . . . and witnessed. Thankfully, her last hours were peaceful. We were with her on a tablet screen as she took her last breath. It was unbearable and unbearably tender. Exhale without an inhale Birth in reverse No Please Just one more Grief is not one thing but in fact it is a dizzy constellation of sensations and feelings during freefall. All losses are different so you can’t pull out the map from the last death and find your way. This one, Milly, mom, feels kaleidoscopic. The terrain and colors are almost too much to behold so I hold them with warm and fleshy hands, hands made for holding the small, delicate hands of a motherless child. Too painful Too beautiful Rest here There is no sugar-coating loss. I don’t yet want to be fixed with heavenly promises and angel choirs. I am heart broken. As Sharon Salzburg says, “Sometimes it just hurts.” I trust grief. It is the medicine for loss—terrible, bitter, tender and sweet. There’s a wisdom I can’t claim but somehow know. Grief is a practice. I show up with as much kindness and compassion as I can. Pull back the covering and see what’s here. Mom is here in the broken places. It is here that I rediscover my blessing which isn’t bone or flesh or breath but is love. I was born in love. I am broken because I was loved so well. I love in return. In brokenness my heart mysteriously blooms, not in my time, but in grief’s good time. Let me lay In the fertile holy soil With the rotting oak leaves And the still sheathed acorn Waiting for rain Waiting for sun Waiting for mom P.S. Please know that I am OK, even when I’m not OK. This time of COVID sequester without life's usual busyness has given this walk with grief more texture and truth. I feel the unexpected miracle of gratitude—eyes that are capable of seeing connection and goodness regardless of condition or circumstance. I have been held and continue to be held in the spiritual arms, both divine and those who wear skin, of boundless compassion. For those of you who knew of mom’s death and those who are hearing this for the first time, thank you for your care and love. One of mom’s favorite stories was of a visiting missionary who told her that we were so rich. She thought it was a strange comment since we were a family of seven living on a small-town preacher’s salary. But he then added, “This family!” As I consider my given and chosen family, I too, feel so rich.

“The capacity of delight is the gift of paying attention.” |

Daily Bites and BlessingsWelcome to "Daily Bites and Blessings." Pull up a chair. I’ve set a place for you at the table. These edibles are sometimes bitter, sometimes sweet and often they are both. This is a come as you are party. I invite you to bring your compassion, courage, and curiosity as we dine together on life's bounty. May our time together give us more light and more love.

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed